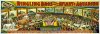

After 146 Years, Ringling Brothers Circus Takes Its Final Bow

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/21/nyregion/ringling-brothers-circus-takes-final-bow.html

UNIONDALE, N.Y. — The lights went up on the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey circus on Sunday evening to reveal 14 lions and tigers sitting in a circle, surrounding a man in a sparkling suit. It was a sight too implausible to seem real yet such an iconic piece of Americana that it was impossible to believe the show would not go on.

After 146 years,

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey is closing for good, responding to a prolonged slump in ticket sales that has rendered the business unsustainable, according to its operator,

Feld Entertainment. On Sunday, the circus glittered, thundered and awed beneath the booms and klieg lights of Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum. That there was no tent over the final show, no striped eaves from which the daring young man on the flying trapeze could hang, felt fitting. The big top was packed up, this time forever.

Autumn Luciano stood outside, ticket in hand. “It feels a little like a funeral today, but I’m trying not to mourn it in a sad way,” said Ms. Luciano, 33, a pinup photographer who had flown in from Lansing, Mich., to see the last show. “Circus is all about being happy.”

She pulled up her sleeve to reveal a tattoo of a circus tent on her wrist. Without circuses, “we lose the ability to go and see that humans can do anything,” she said. “You go to the circus and see human beings doing insane things, but the truth is, we all have the ability to do crazy things.”

This circus began in 1871 as P. T. Barnum’s Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan & Hippodrome, and Feld bought it in 1967. After the removal of elephants from the performance last year after fierce and prolonged condemnation from

animal rights groups, already-falling ticket sales dropped even further. The circus — with its 500-person crew, 100 animals and

mile-long trains, which moved around the trapeze and its artists, the high wire and its tightrope walkers, the motorcycles and the daredevils — had become infeasible in an age in which video games and cellphone screens compete to provide childhood wonder.

When the ringmaster, Johnathan Lee Iverson, first saw the circus as a 9-year-old at Madison Square Garden in Manhattan, he could have sworn that the spangled horses that galloped there were real unicorns. At 41, after nearly two decades with Ringling Brothers, he has an awe in his voice when he speaks of the place that suggests that his certainty endures.

The world is losing “

a place of wonder,” he said at an event a few days before the final performances. All around him, performers with thick makeup and saddened faces spoke to reporters about the circus’s demise. “It’s the last safe space,” he said. “It’s the last pure form of entertainment there is.”

For Ashley Vargas, 30, who worked with the animals and skated in the show, the loss of the elephants, some of which she had tended to from birth, was the beginning of the end. The elephants were retired to the circus’s

sanctuary in Florida.

“To this day, the final performance with the elephants is the hardest performance I have ever had to go through,” she said. “I had to say goodbye to elephants I’d been with since they were born. They were part of my family.”

Beside her, Daniel Eguino clutched the handlebars of the blue motorcycle he rode inside a metal cage called the Globe of Death. Mr. Eguino, 29, the son of a contortionist mother and a father who was a trapeze artist, said he was heartbroken. “Not because they close the show that I work in — it’s that they close history,” he said.

The final show was shot through with moments in which performers broke the fourth wall to reflect on the end. As two tigers sat watching, their master, Alexander Lacey, turned to the crowd. “People are not really concerned with lots of wildlife until they can feel it and see it, enjoy it and love it as much as I do,” he said, urging the audience to support well-run circuses and zoos. “Sorry, boys, I don’t usually do that,” he said turning back to the patient tigers, awaiting their next cues. “I’ve confused you.”

After the trapeze artists fell one by one into the net below their rig at the end of their act, the final two gymnasts walked toward each other in the middle of the net. Suspended above the ground, the two men grasped each other in a long embrace.

Yet in the halls outside the three final performances, which were given consecutively on Sunday, sadness seemed to be banished. Children snatched at souvenir swords, pulled tiger masks over their heads and slurped rainbow snow cones from cups shaped like elephants. The crowd seemed buoyed by the frivolity of the clowns, and the way that a triple flip from the rafters by a glittering young woman onto the shoulders of a beaming young man made anything seem possible. For some, clearly, hope bubbled anew with each big clash of the cymbals.

Many said they believed the circus would somehow return, perhaps retooled and rebranded, a better fit for the age. “If it doesn’t?” said Shawn Goberdhan, 31, a pharmacy manager from Queens carrying his son Lucas, 2, in his arms. “I can’t even think about it.”

Some performers, like Rigoberto Cardenas, 35, a fifth-generation trapeze artist from Chile, worried about what would become of their art after the last pony pranced out of the proverbial big top and the last gymnast took her bow. “New generations of my family, they are not going to see in me what they want to be,” Mr. Cardenas said. “For a circus performer, that’s what you aim to do, to be in the memory of your people for all time.”

Eating popcorn from a candy-striped bag during intermission, William Holden, 59, a hospital administrator from Dover, Del., said change might be good. “It’s the greatest last show on earth,” he said, “but we have to live and change and adapt and keep moving. That’s the beauty of America: We keep changing, and we move on.” He headed back into the show.

Inside the arena, the ringmaster strutted, and the horses — or maybe they were unicorns — galloped by. A few days earlier, Mr. Iverson had said that the end of his career, of the circus, was unthinkable. As long as his top hat was on and he was safe in his jacket with the sparkling epaulets, he could pretend the show would go on.

“You can cry,” Mr. Iverson said, “after the curtain closes.”

As the show finally ended, the backstage crew members, the animal handlers, the performers’ small children and even the train engineers joined the performers on the arena floor, standing with the costumed dancers. They sang a round of “Auld Lang Syne.”

But before that, the people in the crowd rose to their feet for a prolonged ovation. The ringmaster cheered back at them, “You mean the circus isn’t antiquated?” The crowd roared. “You mean you love the circus?” he said. The noise was deafening.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/circus_leaves_town