Well I'm a big ACC fan too but wasn't so keen on the Rama sequels. On the other hand, despite ACC being credited as co-author, I suspect his writing credit was simply for allowing the privilege of writing the sequels.However, I've read the RAMA series through at least four times - and look forward to it again one of these days. I'm just a big ACC fan...

You've got nothing to lose by trying it.

Review 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

- Thread starter Doctor Omega

- Start date

ant-mac

Member: Rank 9

There was definitely a strong ACC presence throughout the sequels, but unfortunately, it was also easy to detect Gentry Lee's presence. He certainly has a much earthier and grittier approach to his fiction writing. I don't mind that in small doses, when it's mixed in with ACC's style, but it does take some adapting to. I found that their combined styles mostly work - for me at least - in the RAMA series.Well I'm a big ACC fan too but wasn't so keen on the Rama sequels. On the other hand, despite ACC being credited as co-author, I suspect his writing credit was simply for allowing the privilege of writing the sequels.

I've always preferred ACC's clinical and detached writing style. It sometimes comes off as slightly aloof or cold, but I love the clarity that also brings. Of course, that's just my own personal impression of him.

Nick91

Member: Rank 2

I've always felt that 2001: A Space Odyssey is like a hybrid between a conventional film and a documentary. The former because the storyline, along with its characters, is fictional. A documentary in the sense that it lacks the entertainment value (sparse dialogue, prolonged sequences) that commercially viable movies aim to have, whilst provides attentive (that is, those who haven't fallen asleep) viewers with something that is thought-provoking, deep and philosphical.

It's not my cup of tea, but I still get why, with such unusual narrative, it has become one of the most memorable and analysed movies in the history of cinema.

It's not my cup of tea, but I still get why, with such unusual narrative, it has become one of the most memorable and analysed movies in the history of cinema.

ant-mac

Member: Rank 9

For me, it is the sparse dialogue and prolonged sequences that makes it so entertaining.I've always felt that 2001: A Space Odyssey is like a hybrid between a conventional film and a documentary. The former because the storyline, along with its characters, is fictional. A documentary in the sense that it lacks the entertainment value (sparse dialogue, prolonged sequences) that commercially viable movies aim to have, whilst provides attentive (that is, those who haven't fallen asleep) viewers with something that is thought-provoking, deep and philosphical.

It's not my cup of tea, but I still get why, with such unusual narrative, it has become one of the most memorable and analysed movies in the history of cinema.

In any case, you could have just described MAD MAX 2 with that description.

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

To remake 2001 would be unthinkable, cinematic blasphemy.

Wonder when Netflix will get round to it?

And what their excuses will be?

Wonder when Netflix will get round to it?

And what their excuses will be?

Funnily enough, I'm not generally a fan of remakes especially not of classics that have aged as well as this one, but for some reason I think I'd be keen to see a Netflix remake of this as a single limited episode series.To remake 2001 would be unthinkable, cinematic blasphemy.

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

JohnnyL REACTS

Member: Rank 1

Boring? It is hypnotic. And brilliant.

That film puts you in a trance. It's meant to be savoured. One of my favourites!

That film puts you in a trance. It's meant to be savoured. One of my favourites!

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

johnnybear

Member: Rank 6

I've never been a big fan of 2001. The story could have been much better and Keir Dullea is another of these American actors that doesn't put much into his performance I've always thought! I did like the sequel 2010 though as I recall, not enough to buy though!

JB

JB

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY - 50th Anniversary | "Standing on the Shoulders of Kubrick" Mini Documentary

Stanley Kubrick's groundbreaking 2001: A Space Odyssey opened the door to all the films and filmmakers who followed it. Through interviews with directors such as George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Sydney Pollack - as well as special effects professionals and cultural historians - this documentary examines the legacy of Kubrick's masterpiece and its influence on science fiction films, special effects and world cinema.

Stanley Kubrick's groundbreaking 2001: A Space Odyssey opened the door to all the films and filmmakers who followed it. Through interviews with directors such as George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Sydney Pollack - as well as special effects professionals and cultural historians - this documentary examines the legacy of Kubrick's masterpiece and its influence on science fiction films, special effects and world cinema.

Last edited:

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

Stanley Kubrick On The Set of 2001: A Space Odyssey

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY - Trailer

2001spaceodysseymovie.com

"For the first time since the original release, this 70mm print was struck from new printing elements made from the original camera negative. This is a true photochemical film recreation. There are no digital tricks, remastered effects, or revisionist edits. This is the unrestored film - that recreates the cinematic event that audiences experienced fifty years ago." - Christopher Nolan Stanley Kubrick’s dazzling, Academy Award®-winning* achievement is a compelling drama of man vs. machine, a stunning meld of music and motion. Kubrick (who co-wrote the screenplay with Arthur C. Clarke) first visits our prehistoric ape-ancestry past, then leaps millennia (via one of the most mind-blowing jump cuts ever) into colonized space, and ultimately whisks astronaut Bowman (Keir Dullea) into uncharted space, perhaps even into immortality. “Open the pod bay doors, HAL.” Let an awesome journey unlike any other begin.

2001spaceodysseymovie.com

"For the first time since the original release, this 70mm print was struck from new printing elements made from the original camera negative. This is a true photochemical film recreation. There are no digital tricks, remastered effects, or revisionist edits. This is the unrestored film - that recreates the cinematic event that audiences experienced fifty years ago." - Christopher Nolan Stanley Kubrick’s dazzling, Academy Award®-winning* achievement is a compelling drama of man vs. machine, a stunning meld of music and motion. Kubrick (who co-wrote the screenplay with Arthur C. Clarke) first visits our prehistoric ape-ancestry past, then leaps millennia (via one of the most mind-blowing jump cuts ever) into colonized space, and ultimately whisks astronaut Bowman (Keir Dullea) into uncharted space, perhaps even into immortality. “Open the pod bay doors, HAL.” Let an awesome journey unlike any other begin.

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

Celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the film’s release, this is the definitive story of the making of 2001: A Space Odyssey, acclaimed today as one of the greatest films ever made, including the inside account of how director Stanley Kubrick and writer Arthur C. Clarke created this cinematic masterpiece.

Regarded as a masterpiece today, 2001: A Space Odyssey received mixed reviews on its 1968 release. Despite the success of Dr. Strangelove, director Stanley Kubrick wasn’t yet recognized as a great filmmaker, and 2001 was radically innovative, with little dialogue and no strong central character. Although some leading critics slammed the film as incomprehensible and self-indulgent, the public lined up to see it. 2001’s resounding commercial success launched the genre of big-budget science fiction spectaculars. Such directors as George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Ridley Scott, and James Cameron have acknowledged its profound influence.

Author Michael Benson explains how 2001 was made, telling the story primarily through the two people most responsible for the film, Kubrick and science fiction legend Arthur C. Clarke. Benson interviewed Clarke many times, and has also spoken at length with Kubrick’s widow, Christiane; with visual effects supervisor Doug Trumbull; with Dan Richter, who played 2001’s leading man-ape; and many others.

A colorful nonfiction narrative packed with memorable characters and remarkable incidents, Space Odyssey provides a 360-degree view of this extraordinary work, tracking the film from Kubrick and Clarke’s first meeting in New York in 1964 through its UK production from 1965-1968, during which some of the most complex sets ever made were merged with visual effects so innovative that they scarcely seem dated today. A concluding chapter examines the film’s legacy as it grew into it current justifiably exalted status.

- Hardcover: 512 pages

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (19 April 2018)

- Language: English

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

Restoration Trailer.....

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

Douglas Rain: Actor who voiced Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey dies

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-46178930

Actor Douglas Rain, who was the voice of the sinister computer Hal in sci-fi film 2001: A Space Odyssey, has died, the organisers of a theatre festival he founded have said.

https://twitter.com/stratfest/status/1061813942110969856/photo/1?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1061813942110969856&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.co.uk%2Fnews%2Fentertainment-arts-46178930

Rain died at the age of 90, according to the Stratford Festival in Canada.

The actor performed for 32 seasons at the Shakespearean festival and was nominated for a Tony Award in 1972.

But he will be best remembered as the voice of Hal 9000, the AI computer in Stanley Kubrick's landmark 1968 film.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

HAL 9000: "I'm sorry Dave, I'm afraid I can't do that"

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-46178930

Actor Douglas Rain, who was the voice of the sinister computer Hal in sci-fi film 2001: A Space Odyssey, has died, the organisers of a theatre festival he founded have said.

https://twitter.com/stratfest/status/1061813942110969856/photo/1?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1061813942110969856&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bbc.co.uk%2Fnews%2Fentertainment-arts-46178930

Rain died at the age of 90, according to the Stratford Festival in Canada.

The actor performed for 32 seasons at the Shakespearean festival and was nominated for a Tony Award in 1972.

But he will be best remembered as the voice of Hal 9000, the AI computer in Stanley Kubrick's landmark 1968 film.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

HAL 9000: "I'm sorry Dave, I'm afraid I can't do that"

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

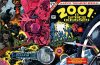

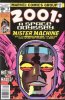

Monthly series

Shortly after the publication of the treasury edition, Kirby continued to explore the concepts of 2001 in a monthly comic book series of the same name, the first issue of which was cover dated December 1976.[4] In this issue, Kirby followed the pattern established in the film. Once again the reader encounters a prehistoric man ("Beast-Killer") who gains new insight upon encountering a Monolithas did Moon-Watcher in the film. The scene then shifts, where a descendant of Beast-Killer is part of a space mission to explore yet another Monolith. When he finds it, this Monolith begins to transform the astronaut into a Star Child, called in the comic a "New Seed".

Issues #1–6 of the series replay the same idea with different characters in different situations, both prehistoric and futuristic. In #7 (June 1977), the comic opens with the birth of a New Seed who then travels the galaxy witnessing the suffering that men cause each other. While the New Seed is unable or unwilling to prevent this devastation, he takes the essence of two doomed lovers and uses it to seed another planet with the potential for human life.[5]

In issue #8 (July 1977), Kirby introduces Mister Machine, who is later renamed Machine Man.[6] Mister Machine is an advanced robot designated X-51. All the other robots in the X series go on a rampage as they achieve sentience and are destroyed. X-51, supported by both the love of his creator Dr. Abel Stack and an encounter with a Monolith, transcends the malfunction that destroyed his siblings. After the death of Dr. Stack, X-51 takes the name Aaron Stack and begins to blend into humanity.[7] Issues #9 and 10, the final issues of the series, continue the story of X-51 as he flees destruction at the hands of the Army

.

Shortly after the publication of the treasury edition, Kirby continued to explore the concepts of 2001 in a monthly comic book series of the same name, the first issue of which was cover dated December 1976.[4] In this issue, Kirby followed the pattern established in the film. Once again the reader encounters a prehistoric man ("Beast-Killer") who gains new insight upon encountering a Monolithas did Moon-Watcher in the film. The scene then shifts, where a descendant of Beast-Killer is part of a space mission to explore yet another Monolith. When he finds it, this Monolith begins to transform the astronaut into a Star Child, called in the comic a "New Seed".

Issues #1–6 of the series replay the same idea with different characters in different situations, both prehistoric and futuristic. In #7 (June 1977), the comic opens with the birth of a New Seed who then travels the galaxy witnessing the suffering that men cause each other. While the New Seed is unable or unwilling to prevent this devastation, he takes the essence of two doomed lovers and uses it to seed another planet with the potential for human life.[5]

In issue #8 (July 1977), Kirby introduces Mister Machine, who is later renamed Machine Man.[6] Mister Machine is an advanced robot designated X-51. All the other robots in the X series go on a rampage as they achieve sentience and are destroyed. X-51, supported by both the love of his creator Dr. Abel Stack and an encounter with a Monolith, transcends the malfunction that destroyed his siblings. After the death of Dr. Stack, X-51 takes the name Aaron Stack and begins to blend into humanity.[7] Issues #9 and 10, the final issues of the series, continue the story of X-51 as he flees destruction at the hands of the Army

.

Doctor Omega

Member: Rank 10

THE CRAZY LEGACY OF JACK KIRBY’S FORGOTTEN 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY

WHEN DIRECTOR STANLEY Kubrick released 2001: A Space Odyssey 50 years ago, he intended it to be a "nonverbal experience." The movie’s dialogue was sparse, and it relied heavily on visuals and score. It was, Kubrick told Playboy in 1968, a subjective film, meant to reach audiences "at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does.

The same cannot be said of its 1976 comic book adaptation. Marvel's oversized Treasury Edition, which was written, drawn, and edited by the late Jack Kirby—legendary co-creator of Captain America, the X-Men, Black Panther, and dozens of others—left little up to interpretation. It followed the film meticulously: 21st century scientists discover a monolith buried on the Moon; astronauts sent to investigate are threatened by HAL 9000; one of those explorers is reborn as Star Child. But while the panels mimicked Kubrick’s shots, the comic also fundamentally subverted 2001, putting in scads of dense text where previously the director’s elegantly silent aesthetic had done all the talking.

The comic adaptation of 2001 was, if nothing else, a conceptual affront to Kubrick’s film. In a way, it had to be—comics panels can’t wordlessly convey the feelings movie scenes can. Creatively, though, Marvel’s 2001 isn’t easily dismissed, even if it has been largely forgotten. It’s a sprawling space adventure that, incredibly, launched a 10-issue spin-off and a new character into the Marvel canon. And that’s thanks entirely to Kirby.

The Origin Story

When Marvel acquired the rights to 2001 from MGM in the mid-1970s, it was about to welcome back its most important architect. Kirby established himself as an undisputed genius by developing (along with Stan Lee) the backbone of Marvel’s Silver Age glory. He left for rival DC Comics in 1970, but six years later returned to Marvel, and when the ink was dry on the contract the news was shared via one of Lee’s Stan’s Soapbox columns. "Jack Kirby is back!" he wrote. "One of Jolly Jack’s first projects will be a Marvel Treasury Edition of (hold onto your hat) 2001: A Space Odyssey!"

"My understanding is that Marvel said, 'Who should do this?,’ and everyone said Kirby," says Mark Evanier, a comic book writer, Kirby friend and colleague, and author of the biography Kirby: King of Comics. Kirby was the right choice for the assignment, but, Evanier says, he was wary of taking on someone else’s story, especially one as iconic as Kubrick’s vision of 2001.

The illustrations were instantly recognizable to anyone who’d seen the film, but the characters were uniquely Kirby's: beefy and emotive with a touch of uncanny.

“He didn’t feel he had a lot of wiggle room to expand or inject himself into it,” Evanier says. “He had to keep reminding himself, ‘That’s my viewpoint, that’s not Stanley Kubrick’s,’ and adjusting.”

To make his comic, Kirby watched 2001 again, referenced a stack of stills, and pulled from the screenplay and Arthur C. Clarke’s novelization. The illustrations were instantly recognizable to anyone who’d seen the film, but the characters were uniquely his: beefy and emotive with a touch of uncanny. There are also moments of pure Kirby: a splash page of a spacesuit-clad astronaut gaping at an exploding cosmic sky, an acid-trip interpretation of the climatic Star Gate sequence.

But then there was all that extra text. Those boxes of exposition, much of it drawn from Clarke’s novel, also filled the pages, erasing some of the film’s mystery and saddling scenes like HAL's terrifying murder of Frank Poole with hand-holding narration.

Evanier estimates it took Kirby three to four weeks to complete the 72-page book. (It was inked by Frank Giacoia, lettered by John Costanza, and colored by Kirby and Marie Severin.) Kirby later said working on 2001 was "an honor, but not a lot of fun," and once it was completed he was ready to move on.

2001: Another Odyssey

Marvel, however, wanted more. 2001 was enough of a hit that the company asked Kirby to develop a monthly follow-up. "He thought the idea of doing the ongoing 2001 series was not a great idea," Evanier says. "But he spent much of his life taking not-great ideas and trying to turn them into good comics." So Kirby got to work.

But there was a hitch. It was unclear if Marvel or MGM would own any original characters introduced in the series. Rather than risk it, Marvel dissuaded Kirby from creating new, recurring characters, and when the title debuted in December 1976 its first four issues were templatized: a prehistoric encounter with the monolith is mirrored by a far-out Space Age encounter that leaves someone being reborn as a new seed.

‘2001 really is Kirby doing the best little fables or stories that are both mythological and science-fictional. It just nails him, in a way. It's pretty great.’

"I think he knew the value of storytelling and mythology and legend and how stories help us make our way through the world," says Randolph Hoppe, acting director of the Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center. "2001 really is Kirby doing the best little fables or stories that are both mythological and science-fictional. It just nails him, in a way. It's pretty great."

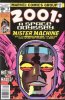

Eventually, though, he rebelled. "Norton of New York 2040 AD," in issues five and six, is classic Kirby—a cross between Marvel’s Inhumans and DC’s New Gods, full of humans in wild future armor battling bizarro monsters and mutants surrounded by infernal machines. And then, in the final three issues, Kirby creates a new character: Machine Man, a purple cyborg originally called Mister Machine who proved so popular Marvel canceled 2001 , gave the character its own books, and introduced it into the general Marvel population.

The Legacy

With Machine Man, Kirby’s 2001 odyssey was finally over—and in 1978 so was his second stint with Marvel. He kept working until his death, at 76, in 1994, and in the intervening years his reputation has solidified as one of comics’ most influential figures. But as Black Panther, Thor, and the X-Men gained popularity, 2001 slid further into obscurity.

"There are no traces of the comic in the Kubrick Archive," says James Fenwick, a Kubrick scholar at De Montfort University. "I'm not sure if Stanley Kubrick ever saw the comics. I did show them to [Kubrick’s brother-in-law and longtime producer] Jan Harlan a couple of years back, and he was intrigued and had never seen them before. I don't think we will ever know if Kubrick saw them."

The chances of improving the work’s reputation are bleak. Thanks to a thicket of legal issues—Marvel’s deal was with MGM, but Warner Bros. now owns the rights to the film, and then there’s the Kubrick estate—the books have never been collected or reissued. Though Hoppe has been trying to drum up interest.

"Let's make one book filled with the color comics, then another filled with the pencil [art], and put them in a slipcase and then you have the big Monolith Edition of Kirby's 2001," he says. "But nobody was able to come back and say, 'I got [the rights], let's go.'"

Hoppe is committed, though, and this weekend the Kirby Museum is staging a 2001-focused pop-up exhibition at New York’s One Art Space. "I'm a little frustrated that no one talks about 2001 and people don't know it," he says. "Hopefully it will get some attention. Maybe somebody will figure who owns the rights."

Evanier acknowledges that 2001 isn’t one of the most important things Kirby did. But he, too, would welcome its return to print—if only to complete the Kirby library.

“In the last few years almost everything Jack did has been reprinted, brought back into print, in deluxe volumes,” he says. “This book, by virtue of being one that has not been reprinted, has a special feel to some people. To a certain extent it's the holy grail for some Kirby fans.”

WHEN DIRECTOR STANLEY Kubrick released 2001: A Space Odyssey 50 years ago, he intended it to be a "nonverbal experience." The movie’s dialogue was sparse, and it relied heavily on visuals and score. It was, Kubrick told Playboy in 1968, a subjective film, meant to reach audiences "at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does.

The same cannot be said of its 1976 comic book adaptation. Marvel's oversized Treasury Edition, which was written, drawn, and edited by the late Jack Kirby—legendary co-creator of Captain America, the X-Men, Black Panther, and dozens of others—left little up to interpretation. It followed the film meticulously: 21st century scientists discover a monolith buried on the Moon; astronauts sent to investigate are threatened by HAL 9000; one of those explorers is reborn as Star Child. But while the panels mimicked Kubrick’s shots, the comic also fundamentally subverted 2001, putting in scads of dense text where previously the director’s elegantly silent aesthetic had done all the talking.

The comic adaptation of 2001 was, if nothing else, a conceptual affront to Kubrick’s film. In a way, it had to be—comics panels can’t wordlessly convey the feelings movie scenes can. Creatively, though, Marvel’s 2001 isn’t easily dismissed, even if it has been largely forgotten. It’s a sprawling space adventure that, incredibly, launched a 10-issue spin-off and a new character into the Marvel canon. And that’s thanks entirely to Kirby.

The Origin Story

When Marvel acquired the rights to 2001 from MGM in the mid-1970s, it was about to welcome back its most important architect. Kirby established himself as an undisputed genius by developing (along with Stan Lee) the backbone of Marvel’s Silver Age glory. He left for rival DC Comics in 1970, but six years later returned to Marvel, and when the ink was dry on the contract the news was shared via one of Lee’s Stan’s Soapbox columns. "Jack Kirby is back!" he wrote. "One of Jolly Jack’s first projects will be a Marvel Treasury Edition of (hold onto your hat) 2001: A Space Odyssey!"

"My understanding is that Marvel said, 'Who should do this?,’ and everyone said Kirby," says Mark Evanier, a comic book writer, Kirby friend and colleague, and author of the biography Kirby: King of Comics. Kirby was the right choice for the assignment, but, Evanier says, he was wary of taking on someone else’s story, especially one as iconic as Kubrick’s vision of 2001.

The illustrations were instantly recognizable to anyone who’d seen the film, but the characters were uniquely Kirby's: beefy and emotive with a touch of uncanny.

“He didn’t feel he had a lot of wiggle room to expand or inject himself into it,” Evanier says. “He had to keep reminding himself, ‘That’s my viewpoint, that’s not Stanley Kubrick’s,’ and adjusting.”

To make his comic, Kirby watched 2001 again, referenced a stack of stills, and pulled from the screenplay and Arthur C. Clarke’s novelization. The illustrations were instantly recognizable to anyone who’d seen the film, but the characters were uniquely his: beefy and emotive with a touch of uncanny. There are also moments of pure Kirby: a splash page of a spacesuit-clad astronaut gaping at an exploding cosmic sky, an acid-trip interpretation of the climatic Star Gate sequence.

But then there was all that extra text. Those boxes of exposition, much of it drawn from Clarke’s novel, also filled the pages, erasing some of the film’s mystery and saddling scenes like HAL's terrifying murder of Frank Poole with hand-holding narration.

Evanier estimates it took Kirby three to four weeks to complete the 72-page book. (It was inked by Frank Giacoia, lettered by John Costanza, and colored by Kirby and Marie Severin.) Kirby later said working on 2001 was "an honor, but not a lot of fun," and once it was completed he was ready to move on.

2001: Another Odyssey

Marvel, however, wanted more. 2001 was enough of a hit that the company asked Kirby to develop a monthly follow-up. "He thought the idea of doing the ongoing 2001 series was not a great idea," Evanier says. "But he spent much of his life taking not-great ideas and trying to turn them into good comics." So Kirby got to work.

But there was a hitch. It was unclear if Marvel or MGM would own any original characters introduced in the series. Rather than risk it, Marvel dissuaded Kirby from creating new, recurring characters, and when the title debuted in December 1976 its first four issues were templatized: a prehistoric encounter with the monolith is mirrored by a far-out Space Age encounter that leaves someone being reborn as a new seed.

‘2001 really is Kirby doing the best little fables or stories that are both mythological and science-fictional. It just nails him, in a way. It's pretty great.’

"I think he knew the value of storytelling and mythology and legend and how stories help us make our way through the world," says Randolph Hoppe, acting director of the Jack Kirby Museum and Research Center. "2001 really is Kirby doing the best little fables or stories that are both mythological and science-fictional. It just nails him, in a way. It's pretty great."

Eventually, though, he rebelled. "Norton of New York 2040 AD," in issues five and six, is classic Kirby—a cross between Marvel’s Inhumans and DC’s New Gods, full of humans in wild future armor battling bizarro monsters and mutants surrounded by infernal machines. And then, in the final three issues, Kirby creates a new character: Machine Man, a purple cyborg originally called Mister Machine who proved so popular Marvel canceled 2001 , gave the character its own books, and introduced it into the general Marvel population.

The Legacy

With Machine Man, Kirby’s 2001 odyssey was finally over—and in 1978 so was his second stint with Marvel. He kept working until his death, at 76, in 1994, and in the intervening years his reputation has solidified as one of comics’ most influential figures. But as Black Panther, Thor, and the X-Men gained popularity, 2001 slid further into obscurity.

"There are no traces of the comic in the Kubrick Archive," says James Fenwick, a Kubrick scholar at De Montfort University. "I'm not sure if Stanley Kubrick ever saw the comics. I did show them to [Kubrick’s brother-in-law and longtime producer] Jan Harlan a couple of years back, and he was intrigued and had never seen them before. I don't think we will ever know if Kubrick saw them."

The chances of improving the work’s reputation are bleak. Thanks to a thicket of legal issues—Marvel’s deal was with MGM, but Warner Bros. now owns the rights to the film, and then there’s the Kubrick estate—the books have never been collected or reissued. Though Hoppe has been trying to drum up interest.

"Let's make one book filled with the color comics, then another filled with the pencil [art], and put them in a slipcase and then you have the big Monolith Edition of Kirby's 2001," he says. "But nobody was able to come back and say, 'I got [the rights], let's go.'"

Hoppe is committed, though, and this weekend the Kirby Museum is staging a 2001-focused pop-up exhibition at New York’s One Art Space. "I'm a little frustrated that no one talks about 2001 and people don't know it," he says. "Hopefully it will get some attention. Maybe somebody will figure who owns the rights."

Evanier acknowledges that 2001 isn’t one of the most important things Kirby did. But he, too, would welcome its return to print—if only to complete the Kirby library.

“In the last few years almost everything Jack did has been reprinted, brought back into print, in deluxe volumes,” he says. “This book, by virtue of being one that has not been reprinted, has a special feel to some people. To a certain extent it's the holy grail for some Kirby fans.”