Rose (the writer), an expert at dramatic construction, has his hero, Juror No. 8 (Fonda in the movie), undermine each of these pieces of evidence individually, assisted along the way by those who’ve defected to the Not Guilty camp. Some items in this impromptu defense are more persuasive than others. The most satisfying, both for its deployment at the climax (it’s the argument that finally convinces E.G. Marshall, playing the most coldly rational juror) and in terms of an appeal to logic, is the observation that the female witness had marks on her nose indicating that she regularly wears eyeglasses, which she wouldn’t have had time to put on when awakened by the victim’s screams in the middle of the night. Far less impressive is the discussion of The Kid’s faulty alibi: Fonda challenges Marshall to account for his actions on each of the last several nights, going back further each time Marshall succeeds, then feels vindicated when Marshall finally gets the title of a film he saw four days earlier slightly wrong (

The Remarkable Mrs. Bainbridge vs.

The Amazing Mrs. Bainbridge) and stumbles over its no-name stars. It wasn’t even the film he’d actually gone to see (which he names without hesitation), but the second feature.

None of this ultimately matters, however, because determining whether a defendant should be convicted or acquitted isn’t—or at least shouldn’t be—a matter of examining each piece of evidence in a vacuum. “Well, there’s some bit of doubt attached to all of them, so I guess that adds up to reasonable doubt.” No. What ensures The Kid’s guilt for practical purposes, though neither the prosecutor nor any of the jurors ever mentions it (and Rose apparently never considered it), is the sheer improbability that

all the evidence is erroneous. You’d have to be the jurisprudential inverse of a national lottery winner to face so many apparently damning coincidences and misidentifications. Or you’d have to be framed, which is what Johnnie Cochran was ultimately forced to argue—not just because of the DNA evidence, but because there’s no other plausible explanation for why

every single detail points to O.J. Simpson’s guilt. But there’s no reason offered in

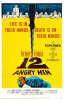

12 Angry Men for why, say, the police would be planting switchblades.

Here’s what has to be true in order for The Kid to be innocent of the murder:

- He coincidentally yelled “I’m gonna kill you!” at his father a few hours before someone else killed him. How many times in your life have you screamed that at your own father? Is it a regular thing?

- The elderly man down the hall, as suggested by Juror No. 9 (Joseph Sweeney), didn’t actually see The Kid, but claimed he had, or perhaps convinced himself he had, out of a desire to feel important.

- The woman across the street saw only a blur without her glasses, yet positively identified The Kid, again, either deliberately lying or confabulating.

- The Kid really did go to the movies, but was so upset by the death of his father and his arrest that all memory of what he saw vanished from his head. (Let’s say you go see Magic Mike tomorrow, then come home to find a parent murdered. However traumatized you are, do you consider it credible that you would be able to offer no description whatsoever of the movie? Not even “male strippers”?

- Somebody else killed The Kid’s father, for reasons completely unknown, but left behind no trace of his presence whatsoever.

- The actual murderer coincidentally used the same knife that The Kid owns.

- The Kid coincidentally happened to lose his knife within hours of his father being stabbed to death with an identical knife.

The last one alone convicts him, frankly. That’s a million-to-one shot, conservatively. In the movie, Fonda dramatically produces a duplicate switchblade that he’d bought in The Kid’s neighborhood (which, by the way, would get him disqualified if the judge learned about it, as jurors aren’t allowed to conduct their own private investigations during a trial), by way of demonstrating that it’s hardly unique. But come on. I don’t own a switchblade, but I do own a wallet, which I think I bought at Target or Ross or some similar chain—I’m sure there are thousands of other guys walking around with the same wallet. But the odds that one of those people will happen to kill my father are minute, to put it mildly. And the odds that I’ll also happen to lose my wallet the same day that a stranger leaves his own, identical wallet behind at the scene of my father’s murder (emptied of all identification, I guess, for this analogy to work; cut me some slack, you get the idea) are essentially zero. Coincidences that wild do happen—there’s a

recorded case of two brothers who were killed a year apart on the same street, each at age 17, each while riding the same bike, each run over by the same cab driver,

carrying the same passenger—but they don’t happen frequently enough for us to seriously consider them as exculpatory evidence. If something that insanely freakish implicates you, you’re just screwed, really.

And that’s just one improbability. In order to vote for acquittal, you would need to accept everything outlined above. Some of these coincidences are individually believable—it’s quite possible that both eyewitnesses honestly convinced themselves they saw The Kid, when they actually just saw a vague figure. But as Bugliosi notes of both Simpson and Oswald, in the real world, you cannot have that much damning evidence pointing at your guilt and still be innocent, unless all of it was deliberately manufactured. (The one place where Bugliosi is shaky is that he won’t concede that

some of the evidence in the Simpson case may have been planted by cops who genuinely believed O.J. was guilty, but wanted to seal the deal.) As stirring as it is to watch Fonda upend his fellow jurors’ assumptions and prejudices, their instincts were sound. The Kid is almost certainly guilty. What a hell of a downbeat, realistic twist ending that would be, eh? Had the movie been made during the Watergate era, maybe that’s how it would have turned out.